BOZEMAN, Mont. – Ben Werner glided up the craggy mountain bowl between Hardscrabble Peak and Frazier Basin in the Bridgers, his heels lifting off his skis with every step. He paused periodically to assess his route up the slope.

Before Werner ascended the bowl, he tested the snow’s stability on a small hill with a similar slant and aspect. He directed his skis toward the hillside and coasted along, looking around for any signs of cracks or slides. The snow held. He continued his path upward.

In backcountry skiing, deciding where to climb up or ski down a slope can be the difference between life and death. And the mountains are deceiving.

Werner would know. He’ll soon release the third edition of his 2011 book, The Bozeman and Big Sky Backcountry Ski Guide. The book documents popular backcountry runs across the Gallatin, Bridger, Madison, Absaroka and Beartooth ranges. Werner has never been caught in an avalanche in the mountains around Bozeman, but he’s witnessed them.

Areas like Mount Ellis in the Gallatins particularly spook Werner because they feel safe. Even though Mount Ellis has no cliffs and looks tame, it avalanches regularly.

“Sometimes it lulls folks into letting their guard down,” Werner said.

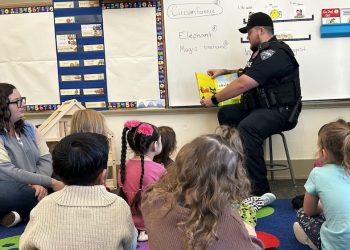

Ski patrollers work to minimize avalanche hazards at ski areas, but backcountry conditions are unmanaged and often dangerous. Whether someone triggers an avalanche often depends on their ability to assess risk and make educated decisions. Whether they survive an avalanche largely depends on their equipment and training.

Officials and experienced backcountry skiers are worried new restrictions at local ski areas could drive more inexperienced people into the backcountry this winter, increasing the risk of avalanche deaths.

Because of COVID-19, Bridger Bowl Ski Area is limiting the number of people allowed on lifts daily, and people with lift tickets and season passes will have to reserve ski days ahead of time. Big Sky Resort is retaining the right to issue daily caps on lift ticket sales, but is not adopting a reservation system. Both mountains are limiting use of lodges.

Doug Chabot, director of Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center, said he predicts restrictions at Bridger Bowl and other ski areas will contribute to a huge increase in backcountry skiing, snowboarding and motorized recreation this winter. Since the pandemic hit Montana in March, popular trailheads around Bozeman, Big Sky, Cooke City and West Yellowstone have seen more traffic than ever before.

“These areas that were always popular are now really, really popular,” Chabot said. “People are enjoying the outdoors, they want to get out more and they’ve invested in gear.”

Chabot worries the influx could result in more avalanche-related deaths and strain search and rescue resources. He hopes the people buying backcountry gear also invest in lifesaving equipment, education and training.

“Typically people will buy gear and get educated somewhere down the line,” Chabot said. “If you want to go into the backcountry, we recommend getting educated first.”

At Uphill Pursuits, a ski shop that specializes in backcountry equipment, sales have increased 500 percent this year from last year, said Riley Siddoway, the managing partner and owner.

The trend isn’t unique to Bozeman. Manufacturers can’t keep up with demand in Colorado, Utah, Montana, Washington, Oregon, Wyoming, California and Nevada, he said.

“They’ve reached a point where some products are just gone,” Siddoway said.

Siddoway has heard many beginners say they want to try backcountry skiing because they’re uncertain about how new restrictions at ski areas will work out.

Siddoway tells them that it’s not as simple as buying new gear. A beacon, probe, shovel and education are necessary components.

“Most people are ready for that, but some people say they weren’t aware of the avalanche part of the equation,” he said.

Avalanches occur when a weak layer in the snowpack fails to hold additional weight, causing the layers above it to fracture and fall down the slope. Sometimes, heavy snow is enough to cause a fracture, but often the additional weight from a person or snowmobile is enough to trigger a slide.

This year, Chabot is communicating with local search and rescue coordinators more than usual. He said people who are new to Montana’s mountains need to understand there’s an expected level of self-sufficiency.

“Realize that when you’re in the backcountry, you’re kind of on your own. Don’t hesitate to call search and rescue, but be prepared to effect your own rescue or spend the night,” Chabot said.

Chabot sees several common threads in avalanche deaths. Victims often fail to recognize signs of instability in the snowpack, don’t travel up risky terrain one at a time or don’t know how to use their rescue gear. People who have practiced using avalanche transceivers and are fit enough to dig someone out quickly have a better chance of saving a life.

“The odds of your partner living are directly correlated in many cases to your ability to dig them out fast,” Chabot said. “If you get someone out in 10 minutes, there’s an 80 percent chance they’ll survive. If you get them out in 20 minutes, your odds are down to 30 percent.”

Scott Secor, commander of the Gallatin County Sheriff’s Office Search and Rescue program, said he’s preparing for an uptick in calls this winter. Visitors seeking to escape COVID-19 restrictions in their hometowns and local skiers and snowboarders seeking to escape restrictions at resorts could increase backcountry use, he said.

This summer, calls to search and rescue did not increase, even though trails were packed with people. Secor suspects this could have been because more people were there to help others execute their own rescues. This could all change once winter rolls around and more rescue situations require a response.

“It’s incredibly important that folks go out and get educated and recreate with others who are experienced and have gone through training,” Secor said. “So many of these accidents and injuries could be avoided with the training that [the avalanche center] provides.”

Secor said winter conditions can be deadly not only for the people being rescued, but for the rescuers themselves. Fewer hours of daylight mean teams are sometimes forced to attempt missions in darkness or in bad weather.

“Whenever a search and rescue team is deployed to save a life, another 20 to 30 rescuers are exposed to the same conditions and dangers,” he said.

Karl Birkeland, director of the National Avalanche Center, said the pandemic adds an additional risk since social distancing is impossible during most missions.

“I believe that puts an even greater responsibility on backcountry users to make good decisions and try and minimize risk,” Birkeland said.

Long-term trends have indicated increased backcountry use doesn’t necessarily lead to more accidents. Over the past 20 to 25 years, there’s been explosive growth in numbers of people heading into the backcountry, but a relatively stable number of avalanche deaths, he said. That’s at least partially because avalanche centers around the country are doing a good job of getting information out to people, and manufacturers are making better rescue gear.

Birkeland doesn’t know whether the long-term trend will carry into this winter. “If we mix all these new users in the backcountry and have a very dangerous and unstable snowpack, we might see a big jump in accidents,” he said.

Fortunately, avalanche center services are widely available. Any number of people can view online avalanche advisories, and because of the pandemic, people can access avalanche awareness courses online.

“If you’re new to the backcountry, make sure you get the avalanche forecast and read it every day, follow the snowpack, figure out what’s going on, carry rescue gear and take an avalanche class,” Birkeland said. “Hopefully in doing so, you can decrease your risk of getting caught in an avalanche this year.”